For some years, I had been searching for an answer to the world’s problems. Having always believed in God, I found it difficult to understand why He would allow the state of humanity to sink to so low a way of life. I had experienced from childhood, in my home in Bermuda, a rigid form of racial discrimination. The schools, cinemas, hotels and even churches practised this evil way of life, which was contrary to the ways of the God I had always believed in; therefore, the search was on for the truth…

Coming to England just after the beginning of the Second World War in October 1939, and finding it absolutely impossible to gain any kind of employment because of my colour, only helped to deepen my lack of belief in the so-called religion that I had been brought up to follow; so I was not looking for religion. I had no idea what I was searching for, yet I knew that as there was a God in whom I had never lost any faith, I felt that there had to be a truth. The words of Christ always stayed with me: ‘Seek and ye shall find’.

I always had a hidden desire to appear on the stage, but as a kid I was extremely shy, yet at the same time always had a great desire to travel. As a young man I found work on a ship plying between Bermuda and New York. I then transferred to another ship called the Eastern Prince, sailing to South America. On our second trip, World War II started. The engine broke down and we all thought we’d been torpedoed after an explosion in the engine room. After repairs in Buenos Aires the British Admiralty recalled the ship, and that brought me to London. It was during my first winter there that I caught pneumonia and very nearly died. I had been washing dishes in a restaurant for about seven weeks. Then one day in March, when the sun was shining brightly and the temperature was that much higher, I decided to leave off a thick green sweater I had been wearing all winter, as well as my overcoat; it was one of those freak days that often occur in England around that time of the year.

During the night the temperature dropped drastically. I came out of the hot kitchen, and caught a chill. The next day, determined to hold on to my job, I went to work with a high fever. The head waiter saw that I wasn’t well and told me to go back home and not to worry about my job – it would still be there when I felt better. I got some cough mixture from the chemist and went to bed.

Later my landlady was so concerned at my sweating and high temperature that she announced, “De Cameron” (as she always called me) “I will call my doctor to have a look at you”. I protested, but she insisted. An Italian doctor soon arrived, said I had a temperature of 104 and would call the ambulance straight away. Again, I protested, but he told me that he would not hear of it. The ambulance came and I was taken to St Pancras Hospital and put in a very large ward. The nurses were nice and friendly, but I had to admit I was not. I was so completely fed up after getting myself straight, with a little money put aside, and then this had to happen. I was told I had pneumonia and pleurisy.

After three or four days of being there, I was not getting any better; in fact, it seemed I was getting much worse. My condition was rapidly deteriorating. I had no appetite and I was not co-operating. At the time of my illness there were many soldiers who were casualties from the evacuation of Dunkirk. They were filling the hospitals throughout the country, so they had little time for a civilian feeling sorry for himself and not trying to get himself better. Soon the staff decided to shift my bed down into the corner of this large ward. I didn’t know why and I didn’t care.

After my second night there, still feeling ill and weak, a night nurse came over to the foot of my bed, looked at my chart and came around to my side and asked how I was feeling. I said, “Not good”. She said I was very ill. “So, I’m ill”, I replied. “Don’t you want to get better?” she enquired. I said “It’s their job to get me better”. “No”, she replied, “it is yours. You are not eating your food. If you don’t eat, you will die. The M and B tablets they are giving you need to have something to feed on”. “So I die”, I retorted. She looked at me. “If you die, they will just send a telegram to your family saying your son passed away here in this hospital”. When she said that, I immediately remembered my mother receiving a letter from my brother, Winslow, in New York saying he had got into some serious trouble. She was standing in the yard of our house with the letter in her hand and crying. I realised I could not do this to her. The tears suddenly started to flow from my eyes and I said, “What can I do to get better?” “Just eat your food”, she said. “You’re young and strong; if you eat, you’ll get better”.

I thanked her and the next morning when the nurse brought the tray to my bed, I forced the porridge down and ate everything. At lunch, I did the same and again at supper. Because of the night nurse, I had acquired a strong desire to get better, get out of the hospital and find a way to go back to my home in Bermuda.

The night after the nurse had come to my bedside, I looked out for her so that I could thank her. There was another nurse on duty and I asked her if the nurse that was on duty last night was around. She said “what other nurse?” “The one that was on last night”, I said. She replied that she was the only nurse that was on duty last night. I didn’t argue with her, but I knew that the person I had talked with the night before and who had no doubt saved my life was someone different. She was much younger, around 21 or 22 years of age. The one on the ward was well into her thirties. I am convinced that she was an angel sent to help me and it was not my time to leave this earth. A couple of days later, they moved my bed back to its original place.

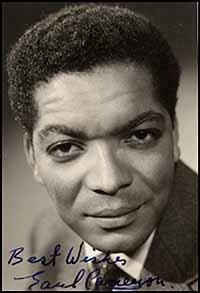

Once I had regained my strength, I went to Liverpool with the hope of joining a ship that would eventually help me to find my way back to Bermuda. Instead I was forced, through circumstances, to join a ship bound for India. It was an Egyptian vessel with mostly Egyptian crew, chartered by the British Government. The conditions on board were dreadful with quarrels and fights taking place most days among the crew. After five months, the ship returned to Liverpool and I made my way back to London. After a few menial jobs as a kitchen porter, I ran into a guy I knew, Harry Crossman. He was in a show called Chu Chin Chow, (circa 1942). He gave me tickets and I went backstage afterwards and said “Harry, I could do what you guys are doing, can’t you get me in the show?” I was happy to do anything in the theatre rather than menial jobs. He said: “No way, the show is already cast”. Then, a couple of weeks later, he came up to me and said, “Earl, your big chance has come. Russell didn’t turn up, it’s the third time he’s missed a matinee”. Robert Atkins, who was directing the show, had told Harry to find somebody else. He took me over to see Robert Atkins who looked me up and down and said “Yeah, Harry, I think he’ll do”! That night I was on stage. I was taken to the dressing room and told what I had to do. That night I was on stage. No rehearsal at all! I put the costume on, and there I was, that very night, performing at the Palace Theatre, Cambridge Circus, London. It was my first time on stage!

My next role was in The Petrified Forest. After nine months in Chu Chin Chow in the chorus and then with some of the friends I met with, it was a big deal to them that I had lines to deliver. I had had no training whatsoever, and was lucky to get such a nice little part. In 1944, I got a good part in All God’s Chillun at Colchester Repertory Theatre. I was learning about the profession. In 1945 I helped form a song and dance act called ‘The Duchess and the Two Dukes’. After that, I went as part of ENSA, the armed forces Entertainments National Service Association tour to India with Leslie Jiver Hutchinson’s band, who were well-known at that time, having many West Indian musicians.

That following year, impresario H.M. Tennent, who put on The Petrified Forest wrote to me and said they were doing a play called Deep Are the Roots. They asked if I would like to be an understudy to Gordon Heath who played the main part. I found that rather nice because even then I wouldn’t have called myself an actor in the true sense of the word. Although I had done quite a lot in the theatre, I had not done anything really outstanding or demanding as an actor.

I went to see them and got the understudy job and we opened in 1947 and went on a pre-West End tour. I soon realised at rehearsal how bad my diction was. The stage manager said to me, ‘Earl, I’m sitting in the fifth row and I can’t understand a word you’re saying’. It was very embarrassing. By chance, I was introduced by one of the cast to a lovely lady, Ms. Amanda Ira Aldridge, a very renowned speech therapist. She was the daughter of the well-known African-American actor, Ira Aldridge, and was in her late seventies at the time. Her father had played many of the great Shakespearean roles, Lear, Othello of course, and Macbeth amongst others. Ms Aldridge gave me elocution lessons and helped me greatly. Later, I went on to study with Cecily Berry, as well as Iris Warren who had a prophylactic method of voice training.

In 1949, my first break came in films. Like most actors, I had been knocking on the door of the film industry. At the time, I was in a play which I hated called Thirteen Death Street Harlem. I was not being paid very well as the show was losing money before I joined it. The producer said that as soon as takings picked up, he would pay me the money I had asked for. Not holding out much hope, I decided to ‘phone a girl I knew who was working for a film company. She mentioned that Ealing Studios were planning to make a picture called Where No Vultures Fly in Kenya. I took the bull by the horns and phoned the casting director, Margaret Harper Nelson. She said they would not be shooting the film until November. I had told her my name and she said, ‘Look, I have seen your picture in Spotlight (a magazine listing actors and actresses) and you would be right for a part we are planning to shoot starting next month. The film is called Pool of London. After two or three tests for the part of Johnny, Basil Deardon, the Director, ‘phoned to say, “We have decided on you for the part”. This was music to my ears. At last, I could say goodbye to Thirteen Death Street Harlem.

After Pool of London, I appeared in several films such as Emergency Call, Sapphire, Safari, Adongo and Simba but I was still doing theatre including Foxhole in the Parlour with Dirk Bogarde at the New Lindsay; the play also appeared on Broadway with Montgomery Clift. Then I had a wonderful part in The End Begins at the Kew Theatre. Among all of this, I was still doing Deep Are the Roots, going from ‘Guest Artist’ to ‘Guest Star’!

In 1952, I went to Rome in search of a part in a film. Rome had become the swinging city for the movie industry. Many of the top actors from Hollywood and Britain had gathered there and like myself were looking for parts; the big stars appeared regularly in film productions.

After a few weeks of searching, I was fortunate enough to land a nice supporting role in a film called La Grande Speranza, later called Torpedo Zone, which allowed me to stay a further five months in the eternal city. Here, I thought, I should find the answer to that truth I was looking for, although, as I said, I was not seeking any kind of religion as I had long lost faith in the institution of the church. However, I still felt that as churches had been built in the name of God, I could hopefully find guidance in one of them and often, when walking through the streets of Rome, I would enter one of the empty churches and kneel and ask God for some kind of answer. But I would find nothing…

I made it a practice to walk most Saturday mornings to St Peter’s Church which was about 40 minutes from where I was staying and say some kind of prayer, feeling hopeful that this highly esteemed edifice would give me the answer, but to no avail. Eventually, I returned to London and got on with my life.

It was while I was in repertory theatre in Halifax, Yorkshire, that I met Audrey. She was a budding actress and I was a guest actor. We started rehearsals for Deep are the Roots, in which we were appearing together. At the time, Audrey was in a play called Scandalmongers. It was a very unpleasant part and I was impressed by how convincing she was in the role and how different she was the next day from the part she had played the night before. Right from the start I was intensely attracted to her and we enjoyed our rehearsals for Deep are the Roots. Indeed our friendship started right from that first day of rehearsal, developing into courtship and then marriage.

In 1963, I was offered a part in a ‘Tarzan’ movie to be made in Thailand. A friend of mine who knew I had been searching for some kind of answer said that I was lucky to be going to this country as he thought Thai people had the answer to life. I had no such impression, although I thought perhaps Buddhism could satisfy my longing for an answer. Strangely enough, I was playing a Buddhist monk in the film as the story revolved around religion. In fact, when the unit was filming on and around the temples, I would be secretly offering some kind of prayer, asking God to give me the answer. Sadly, I received no answer and returned to England somewhat disappointed.

Some two months later, I got a call from an old school friend from Bermuda, Roy Stines. He was visiting London to attend the Centenary of the Bahá’í Faith that was being held at the Royal Albert Hall. I was initially cynical. Although I had been searching for some years for answers to the world’s problems, I wasn’t looking for any type of religion per se. There are so many misunderstandings about the word ‘religion’. My argument was ‘don’t tell me about religion’. With all that is going on, religion has a dirty name these days. At first, I displayed no interest in attending the event, believing it to be attended by ‘fuddy duddy’ so-called religious people with whom I would have little in common. It was Audrey who encouraged me to attend and thank goodness she did as it was my first introduction to a Faith that was to change our lives for the better.

At the time, I was a member of the Rosicrucian Order, but was not fully convinced that this movement would change the world or provide the answers I was looking for. Roy proceeded to lend me the books Thief in the Night’and Bahá’u’lláh and the new Era. We met quite a few times and we would discuss the Faith at length. I read the best part of these two books and we would continue to discuss the Faith. I had plenty to ask him!

When Roy and I arrived for the public meeting at the Royal Albert Hall on the night in question (Hand of the Cause William Sears was the speaker), I was enthralled to see all the radiant faces. I turned to Roy and said: “This is different, the people are different”. There were something like 6,000 people there. What I had expected was a lot of rather bland-looking faces which was what I had formerly experienced on a Good Friday when I was desperately in need of some kind of spiritual sustenance. At the time, I had ventured into a church near to where we were living only to find a congregation of people who appeared to be somewhat down-hearted and certainly not as happy, cheerful and so full of joy as the scene that evening at the Royal Albert Hall.

We arrived about 20 minutes before the start so we went to the cafe area. While standing at the counter, an African-American said to me “Isn’t it fantastic? Isn’t it great?” I replied: “Yes, it’s wonderful!” I added that I wasn’t a Bahá’í. He replied cheerfully, “Oh yes, you are, you just don’t know it yet”.

John Long gave an introduction as Chairman of the NSA, then Philip Hainsworth gave a wonderful talk about Uganda. Philip said that 74,000 people in Uganda had become Bahá’ís. Then I heard a most brilliant talk by Hand of the Cause William Sears and the evening drew to a close. On returning home, I couldn’t wait to tell Audrey about the experience. About three months later, we started going to the Bahá’í Centre at Rutland Gate almost every Thursday night and we were getting very close to declaring our belief in Bahá’u’lláh.

One night, Meherangiz Munsiff wanted us to come to her place on a Sunday. On the way there, I said to Audrey “You do know why she is inviting us, don’t you?” Audrey said: “Of course I do”. At this stage, we were almost ready to become Bahá’ís. After a marvellous evening at Meherangiz’s home, and after a lovely dinner, she produced the Will and Testament of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and we read it right to the end. Wonderful Meherangiz said: “How do you feel?” as she put two declaration cards down in front of us. Audrey signed her card immediately. I was about to sign mine when I suddenly turned to Meherangiz and said: “By the way, I should mention that I am a member of the Rosicrucian Order” and straight away she said: “Well, you will have to give that up, won’t you?” I asked why. She explained that it was a secret society. I didn’t know that; I knew that the Masons were a secret society and they couldn’t be Bahá’ís. I looked up, thinking “What should I do?” and there was a picture of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on the mantelpiece and He looked at me as if to say: “Are you going to let this stand in your way?” Perhaps it was an illusion? Anyway I signed the card and I gave up the Rosicrucians. That night, Audrey and I became Bahá’ís.

We started going to firesides regularly and were living in Richmond upon Thames at that time. Nine months later we moved to South Kensington. Audrey became Secretary, and Mr Youssefian was Chairman of the Spiritual Assembly of Kensington and Chelsea. After a while we made a home front pioneering move to Ealing, which was then able to form an Assembly. Audrey became Secretary and I, Chairman. The other members were Vivian and Ron Roe, Mr and Mrs Fazaneh, Mr and Mrs Youssefian, and Mrs Khoshbin. At that time, Jane, our eldest, was 12, Simon 10, Helen 9, Serena 7, and Phillipa 2.

We stayed in Ealing for about 9 years, then we moved to Welwyn Hatfield community and were there for some 3 years. We were anxious to pioneer, but didn’t know how to go about it. We had pioneered to Ealing, had made up the nine there and also had done the same for Welwyn Hatfield. We were now eager to pioneer overseas. Whilst we were in Welwyn, we got to know the mother of Suhayl Ala’i’, Bahá’í Counsellor in Samoa, who once said, “why don’t you go to the Pacific?” We thought it was an awfully long way, but we said we’d think about it. She said she would write to her son about this. He contacted us and said he was coming through London. We discussed the money situation, and it was decided that at that time we wouldn’t be able to finance the move. Then, a couple of years later, Suhayl came through London again and said he would like to see us. We talked about the possibility of going to Samoa, but he told us about the Solomon Islands.

We then received a letter from Bruce Saunders, an Australian living in the Solomon Islands. He told us about an ice cream business that was up for sale in Honiara, the capital. We thought about this carefully. House prices had risen in the meantime, and if we sold the house in Ealing we would be able to afford our pioneer move to the Solomons.

I took a trip out there in 1978 to have a look at the business. All the equipment was obsolete so I had to replace it. I spent a couple of months there. I kept asking myself all the time: “Am I doing the right thing here?” The Solomons was a pretty primitive place by Western standards.

On arrival, Bruce picked me up at the airport. The Bahá’ís were in the process of building a new Bahá’í centre as the old one was very dilapidated; Bruce said that could be where I could sleep. I have a phobia about rats and I concluded that the place was bound to have rats; there was no way I could spend the night there. An American Bahá’í, Bob Darlow, offered me accommodation and I ended up staying with his family for a couple of months. During that time, I kept asking myself whether I was making the right move or not.

The owners wanted $22,000 for the ice cream business, ‘The Dairy’. The owner had gone into shipping and had become a millionaire. He said: “I believe you are interested in The Dairy”. I said, “yes, of course I am, but your price is too high”. I figured I would offer such a low price he couldn’t possibly accept it and I would be back on the next plane with my conscience clear. He said, “What price have you got in mind?” I said the most I would pay for it would be about $11,000. He immediately rejected my offer and I thought I could go home on the next plane. Two days later, he ‘phoned and said that he would accept the offer. At the time, I didn’t have the money as I would have to go back to England and sell the house. He wasn’t happy about this and he was about to put the ‘For Sale’ sign up again when a friend, Mrs Blum, offered to provide the deposit. There was then no way of getting out of it! I returned home, sold the house, and our family moved to the Solomons and lived there for 15 years.

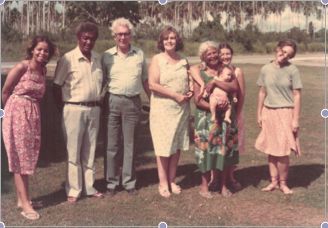

Earl and Audrey with daughters Serena and Phillipa, c.1982. Standing between Earl and Audrey is Owen Battrick

After 11 years in Honiara, Audrey returned to England to be with Phillipa, my youngest daughter so that she could attend drama school. Several months later, Audrey discovered she had breast cancer. I immediately flew back to London to be with her for nine months, while Jane took over running the ice cream business. On my return to Honiara, Jane and her daughter, Louisa, then flew to London to be with Audrey. Whilst finalising my plans to return again to the UK, Jane rang to say “Dad, you’ve got to come back; Mummy is very ill”. I returned, and nine days later Audrey passed away, which devastated us all. My son Simon is still in Honiara; the ice cream business was sold to some Japanese people.

After Audrey passed away, I went to Bermuda with Phillipa. On the very first night, the Bahá’ís had a little gathering and I ran into Barbara, one of the English Bahá’ís, resident in Bermuda. We saw each other a few times, and then a few months later we decided to get married in London. Roy Stines, who guided me to the Faith, had passed away, and Barbara had become a Bahá’í in his wife Vivian’s house.

Today I live a quiet life in Kenilworth, Warwickshire, serving the Faith as far as I am able at the grand old age of 97. I have a lot to be grateful for, but uppermost in my mind is the wonderful bounty our family has received in finding this blessed Faith.

_______________

Earl Cameron

Warwickshire, 2014

Earl Cameron after being awarded the CBE at Buckingham Palace (2009)

with his wife Barbara and daughters Serena and Jane

Earl Cameron being awarded the degree of Honorary Doctor of Letters

(Hon DLitt) by the University of Warwick in January 2013

Earl passed away on 3 July 2020, at the age of 102 years.

What a truly remarkable story of faith and certitude, and your services over the years! I have fond memories of meeting you and Audrey, and of course your beautiful children, in the mid 1960s, mostly at 27 Rutland Gate. Everybody knew the Camerons, you were literally household names in the London Baha’i community. The children were the star performers at many events, reciting prayers, singing songs and dancing, under the watchful eye of Audrey.

There were also many unforgettable times when the friends would gather in your apartment in South Kensington, all welcomed with open arms and enjoying your hospitality, and above all the love and attention you showered on each and every one. How we loved those precious, happy moments!

And then, years later in 1978, we were delighted that you and Counsellor Owen Battrick visited us briefly in our home in Lae, Papua New Guinea, almost like it was meant to be, it just happened, a wonderful surprise indeed!

Thank you, thank you Earl for sharing your life story. I am so pleased that it was my privilege to have met you and your dear family during the time I lived in London, and I will always cherish your friendship. You are the man for all seasons, God bless you forever!

Just wonderful xx

Dearest Earl,

I LOVED reading your story particularly about your early life! You have played such an important part in so many of our lives. Our family has such wonderful memories. Both homes in Kensington and Ealing were our home. Any time we passed through London the doors were open and we were lovingly received as a member of the family. Your children are a credit to both you and Audrey. Little personal note: as a young star-struck teenager I used to take great pride in telling my friends that my friend Earl Cameron was a very good friend of Sidney Poitier!

Deepest love to you

Dear Earl, You were after my darling Vivian the most spiritual and humble person that I came across in my early years as a Baha’i. Knowing you has been a privilige, and still is…… We often used to cross swords with ideas about serving the faith, but the Truth always prevailed and we both learned from it. We could do with you back here to brighten our souls, You are missed very much by your older friends down South. You taught me what true humility is Love Ron Roe of Ealing Baha’is

Wonderful story! He gave up a life on the stage to become an ice cream salesman – all for the Faith?!

I will always owe a huge debt of gratitude for what Audrey and Earl did for me during my first years as a fledgling Baha’i in London, until I moved to Canada in 1971. Our friendship still continues. Thank you, Earl, for sharing these reminiscences.

Dear wonderful Earl. You won’t remember me, but my late husband Foad had lunch with you in North Wales at National Convention some years ago and Foad reminded me of a time in London, before I was ever a Bahá’í, when you were on stage and there was a beautiful lady with you. She was a speaker on stage and an American man stood up and asked her “But would you allow your daughter to marry a black man?”; she turned around and called you “Darling” to introduce you as her husband. I have never forgotten this and she made a big impression upon me then.. Love you

Dianne

Pingback: John Lester | UK Baha'i Histories

As a student in London in 1976, I attended the meetings at the Camerons’ home in Ealing frequently. Wonderful memories. Thank you and happy birthday to Earl Cameron – one day late!

Many Happy Returns on your 100th birthday. I remember first meeting you as a relatively new Bahaí and being so impressed by your relaxed attitude. I also thought of you as a man who was truly happy with himself and what he believed go well my dear dear friend! Derek

Pingback: Sharon Forghani | UK Baha'i Histories

A truly remarkable human being has left this world

Pingback: Bermudian Earl Cameron, ‘Britain’s first black film star’, dies aged 102 – Repeating Islands

Pingback: Earl Cameron, 'Britain's first black film star', dies aged 102 - Angle News

Pingback: Audrey Cameron (1923-1994) | UK Baha'i Histories

Pingback: Earl Cameron, ‘Britain’s first black film star’, dies aged 102 - News Readly

Surely you meant 1917-2020 😊

Oops

Watched him in films, l did not know his name. Xx

Pingback: Colleen MacLeod | UK Baha'i Histories

Pingback: Sara Lindsay | UK Baha'i Histories

Pingback: Sara Lindsay | UK Baha'i Histories - Bahai Journal